BLOG

Rebranding After Acquisition: how to launch a successful rebranding strategy

The mergers and acquisitions sector could quite easily be described as an industry of failures.

Many studies over the past decade have placed the failure rate of mergers and acquisitions at a minimum of 50 percent. Harvard Business Review, for instance, found that only 10-30% of M&A activity results in success.

This high risk of failure for companies venturing into M&A is troubling in light of the sustained impact of 2020. While the mergers and acquisitions market initially appeared to plummet from its 2019 global value of $3.7 trillion, experts are now predicting that COVID accelerated, rather than hampered, long-term M&A growth.

Major 2020 trends such as a worldwide remote workforce, an estimated 19% global increase in online shoppers, and fickle purchasing behaviors, created an environment where brands were either forced to merge to survive or presented with exciting new M&A opportunities for growth.

Read next: Corporate rebranding process

Examples of the latter include Just Eat Takeaway’s acquisition of Grubhub for $7.3 billion, which created the world’s largest online food delivery company outside China. The following month, Uber signed a $2.65 billion deal to acquire Postmates, and most recently, Salesforce bought tech innovators Slack in a $27.7 billion megadeal.

With takeovers seemingly immune to the effects of the pandemic, there’s clearly still a lot to play for in the M&A world. So with so much at stake, how are businesses getting their strategy for mergers and acquisitions so wrong? Two words come to mind – rebranding strategy.

In this article

3 things Brand leaders wish they knew before rebranding

Are you ready to rebrand? Don’t miss these steps

Summary

How to successfully rebrand

One fundamental element of successful brand mergers and acquisitions is a strong rebranding strategy. To demonstrate how a smart, well-planned, and future-proof rebranding strategy holds the key to success, we’ve compiled a list of brand merger examples of businesses that have got their M&A move right and those that did not.

Amazon and Whole Foods: The problem with love at first sight

Image source: Supermarket News

A timeless brand transition example that outlines what could go wrong in a brand merger or acquisition is the case of Amazon’s 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods.

When Amazon announced their $13.7 billion takeover of Whole Foods, Whole Foods CEO John Mackey couldn’t hide his enthusiasm. Describing the union as “love at first sight,” Mackey detailed how Amazon’s intervention had the potential to reverse the company’s recent declining sales, enabling the organic grocer to lower their prices while scaling up to secure more market share.

Amazon, too, had much to gain from merging companies. The e-commerce giant could finally move into the physical world, selling produce in hundreds of stores while collecting all-important shopper data that bolstered its current offering.

Despite industry commentators warning that the acquisition was “the corporate equivalent of mixing tap water with organic extra virgin olive oil,” the future looked promising for the two enterprises.

Fast forward a year, and the Amazon-Whole Foods brand merger/love story had turned extremely sour. Whole Foods employers were reportedly crying on the job and publicly accusing Amazon of turning them into ‘robots.’ Workers even began unionizing to protect jobs they felt were under threat.

With the conflict between Whole Foods employees and Amazon management and stakeholders playing out across newspaper and web pages, what became strikingly obvious was how detrimental a lack of consideration towards the two very different work cultures had become.

Amazon’s fast, easy and efficient services are hugely dependent on a strict internal culture of tight employee discipline, cost-cutting operations, and productivity-driving strategies. In stark comparison, Whole Foods is known for its personal touch, giving stores and employees a level of autonomy and decision-making.

Image source: Geekwire

By forcing a regimented model onto a previously empowered workforce, unsurprisingly Jeff Bezos and co. inevitably found themselves in the category of problematic acquisition examples.

What the Amazon-Whole Foods saga highlights is the risk companies face when financial gains and the bottom line are prioritized over other essential business goals, like the aligning of two distinct internal company cultures. Short-term profits may follow a new logo, new name, enhanced brand messaging, new products, or company restructuring. However, if brand values and identities don’t align with long-term business objectives, a deal is set up for inevitable failure.

L’Oréal: the beauty of the acquisition

As a sector shaped by an ‘acquire or be acquired’ model, the beauty industry is a hotbed for M&A activity, with 2019’s booming acquisition rates taking only a minor COVID hit thanks to a series of high-profile billion-dollar deals.

At the helm of the global beauty M&A scene is French powerhouse L’Oréal. The 111-year-old enterprise is the world’s largest cosmetics brand with a current market value of $29.4 billion, much of which has been generated from decades of targeted mergers and acquisitions.

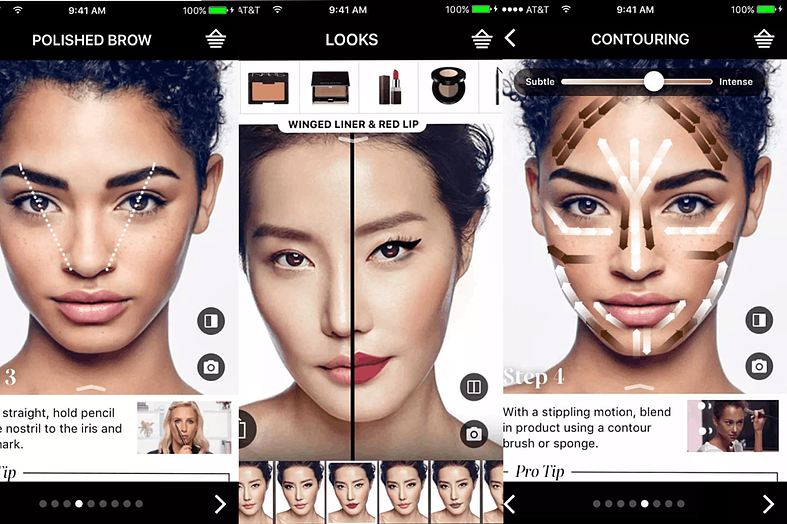

Image source: L’Oreal

The latest of these acquired companies include L’Oréal’s takeover of major AR beauty player Modiface, luxe label Valentino and Japanese dermatology company Takami Co.

These recent partnerships join a long line of strategic acquisitions, such as the $1.3 billion takeover of CeraVe, AcneFree, and Ambi skin-care in January 2017, which doubled the size of L’Oréal’s Active Cosmetics Division in the U.S.

For those outside of industry intel, it’s hardly surprising that L’Oréal holds the title of the world’s largest beauty company. A long history of branding investment paired with strategic advertising, evolving marketing strategies, and A-list endorsed products has made L’Oréal a household name. What comes as more of a surprise is that L’Oréal’s success lies with a portfolio of over 36 international brands, with all but one completely acquired.

From Yves Saint Laurent and Giorgio Armani to Maybelline and ABB (African Beauty Brands), each acquisition on L’Oréal’s books has a distinct, individual, and powerful corporate identity. Merging two brands never looks the same under L’Oréal’s watch, and the L’Oréal brand itself is always kept entirely separate from an acquired brand.

It is this empowerment of the individual brand rather than drastic rebranding after acquisition that CEO Jean-Paul Agon pinpoints as central to L’Oréal’s success: “We offer [acquired brands] the total respect of the identity, culture, spirit, and soul of the brand.”

In an interview with Fortune magazine, Agon built on this importance of the brand, citing Kiehl’s as a prime example of L’Oréal’s merger rebranding strategy. Acquired in 2000, Kiehl’s consisted primarily of a flagship NYC store and had an annual turnover of $20 million. Eighteen years later, Kiehl’s is now a global entity valued at $1 billion.

Speaking of its billion-dollar transformation, Agon is quick to emphasize that L’Oréal’s corporate branding strategy was heavily focused on developing Kiehl’s original brand values and not transforming it into a new company: “When you go to a Kiehl’s store today anywhere in the world – in Korea, China, France, Argentina – it is exactly the replica of the spirit, of the soul, of the identity, of the Kiehl’s store we bought years ago. We have been more than loyal and cultivated the spirit of the brand.”

When implementing their rebranding strategy for mergers and acquisitions of an existing brand, L’Oréal prioritizes, rather than sidelines, investment in brand identity design. In most cases, that includes retaining the company name, signage, and value proposition. As Agon surmises: “the way we grow is exactly this combination of buy and grow. It’s not buy or grow… Once the brands have been acquired, they are brands that we build.”

This ‘buy and grow’ approach has allowed L’Oréal to dominate the beauty world, reach new consumer groups (under different brand names) , secure innovative technologies, and access niche markets with a growing list of diverse acquisitions.

At the helm of the global beauty M&A scene is French powerhouse L’Oréal. The 111-year-old enterprise is the world’s largest cosmetics brand with a current market value of $29.4 billion, much of which has been generated from decades of targeted mergers and acquisitions.

Read how Coloplast managed to streamline their brand relaunch:

EE: starting with a level playing field

While successful brand management for acquisitions is challenging, the world of rebranding after a merger is generally even more complex.

In fact, there are few successful brand merger examples in which two brands’ businesses, cultures, and teams have come together in a joint venture, and both retained equal influence and power.

Take the telecommunications industry; when the launch of Apple’s iPhone collided with the rise of an online marketplace, the high street telecoms industry was destined for decline, forcing previously triumphant brands into a string of mergers and acquisitions.

AT&T’s acquisition of BellSouth and Vodafone’s acquisition of German company Mannesmann, which took place at the height of the .com bubble, remain two of the biggest mergers of all time, worth $86 billion and $180 billion, respectively. These famous corporate branding examples saw two household names, BellSouth and Mannesmann, completely disappear, and Vodafone eventually plunged into massive losses.

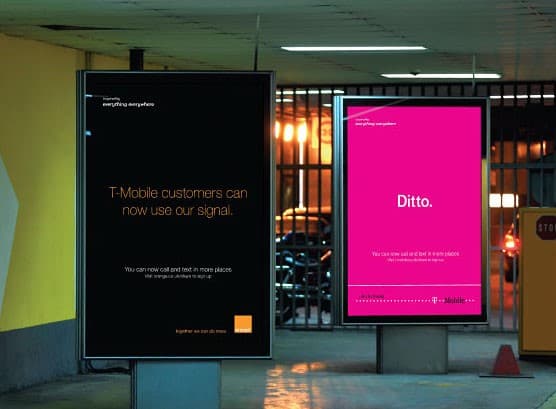

Two brands renowned for bucking this telecoms trend are Orange and Deutsche Telekom’s T-Mobile, two of the biggest UK household names in the 2000s.

“The future’s bright, the future’s Orange” is among the most famous straplines in advertising history and saw the brand build huge equity over two decades. T-Mobile’s marketing team claimed equal fame with marketing activity such as the ‘flashmob,’ which is now the go-to option for any brand trying to make a viral video.

Showing other brands how to merge two brands successfully, this brand transition example set out to be truly collaborative from the very start, as seen in Orange and T-Mobile’s £4m co-branded ad campaign.

Easing consumers and staff into the partnership, the global entities announced their union in a rare joint message that retained and communicated each of the two brand’s recognizable corporate visual identities. This remarkably transparent and candid approach retained and even built on the brand equity each company had established over the years.

Image source: Campaign Live

Image source: Campaign Live

A year on, and the clever merger branding strategy proved a key stage in what would be a longer-term rebrand launch strategy, culminating in the two brands forming EE (a new brand launched around 4G technology with an enormous amount of marketing effort and fronted by Hollywood superstar, Kevin Bacon.)

EE’s launch was deemed a success thanks to well-thought-through brand architecture built on five long years of a carefully planned rebranding strategy focused on long-term stability. This diligence underpins the venture’s ongoing success in today’s telecoms market.

The telecommunications industry in the 2000s serves up key learnings for any sector in a state of contraction and decline. The commercial opportunities of consolidation through mergers and acquisitions are great, but any business with a poorly planned merger rebranding strategy has the potential to see long-established brand equity wiped out overnight.

Editor’s note: How top brand recoup the cost of rebranding their business

The last mile in brand management

Protect your brand

Successful rebranding

These acquisition and brand merger examples make it clear that to be successful and survive in the M&A industry, all parties need to be dedicated to strategic and long-term rebranding efforts.

In any instance of brand worlds merging, building and maintaining this new brand is a continuous and long-term process that goes beyond a logo refresh, font changes, press releases, name changes, changes in brand positioning, or new brand slogan.

At Templafy, we know this process starts with internal implementation. Just one look at L’Oréal’s internal brand culture, and you understand the importance of having a team that works together towards a united goal and is empowered through the support of their employer.

Effective internal employee buy-in starts by giving your employees the resources (i.e., templates, marketing materials, new entity identity, etc.) they need to correctly implement the new branding elements involved in rebranding a company.